What is a land patent?

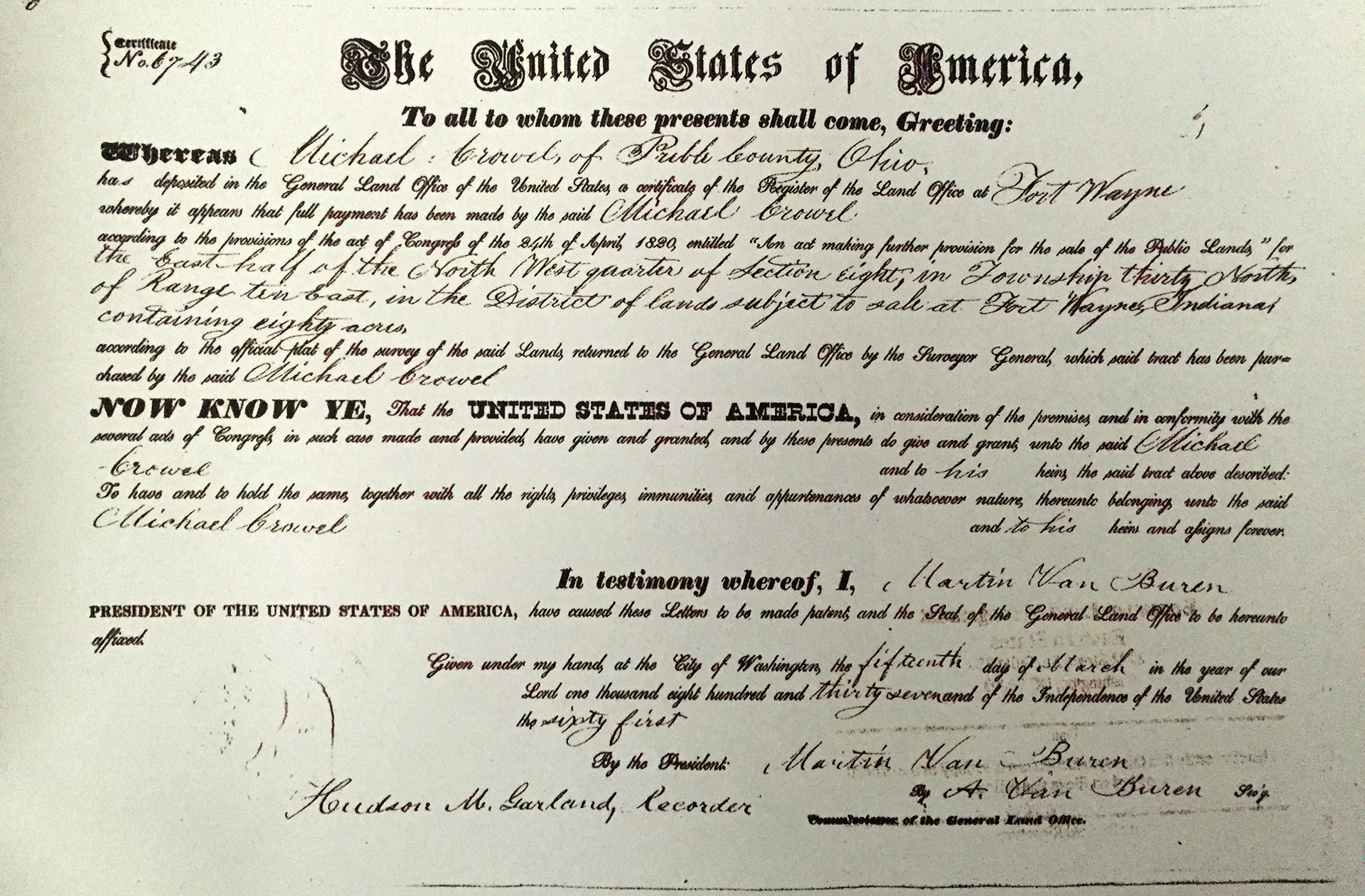

A land patent is the original title granted by the federal government (often signed by a U.S. President) to an individual or entity. It is the highest form of title available under U.S. law, originating from public domain land — land once owned by the United States before being privatized.

A patent for land is the highest evidence of title and is conclusive as evidence even against the government and all others claiming under junior patents or titles (warranty deed), etc. United States v. Stone, 2 US 525, is hereby noticed and has been maintained as against a municipal corporation (County), Beadle v. Smyser, 209 US 393.

In the de jure united states of America and under the Common Law, the land patent is the highest evidence of title for the sovereign "American" Citizen, the evidence of allodial title and true ownership.

Did you know that you can't own land if you are a U.S. citizen? Look at your warranty deed; you're only a tenant. You must bring your original land patent forward in your name and have it recorded. But before you start the land patent process, you must complete the first three steps in The Remedy section of this site. You will need to change your political status from U.S. citizen to a national, property (U.S. citizen) can't own property.

A little bit of history

Land patents began in America before the Revolutionary War. At the end of that war, negotiations were conducted to stop investing in war and instead return to peace, trade, and commerce. Several treaties were reached between the people, the British Crown, and the Pope in Rome. Our sovereign land and our sovereign rights were acknowledged and protected in the settlements, and from there the Constitutions were constructed. When the land was granted to the people of this country, it was all described accurately by metes and bounds on an allodial title called a land patent. These land patents were issued under the authority of international treaty law then managed and protected by the Constitutions, which means that land patents are contracts under a very high lawful authority, much higher than that of real estate or real property. The land patents also include the infamous “forever clause”: “...to the heirs and assigns forever."

With land patents being a true title (not a warranty deed or certificate of title) that includes a forever clause, the founders intended these land patents for you because they assured that even the poorest farmer could not be separated from their land by bankers, politicians, or attorneys.

For a long time this nation “We the People” have believed that we are a free nation and have freedom of liberty and Justice for all. We have believed that we own our property and have certain unalienable rights; that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. That was true at one point in time but as time past we lost a lot of what we had through the change of language usage. Language usage created what is known as Color of Law. Under Color of Law you have home loan, foreclosure, taxes, eminent domain, and encroachment on you. Our entire society today lives under Color of Law.

For the question, what is a Land Patent? A land patent is the first absolute title to land given by the United States of America to the bona fide purchaser or Homestead such titles are called “Allodial”. When the public lands were sold, land "patents" were issued. The patents are absolute title transferring land ownership from a sovereign (the United States of America Government) to a bona fide purchaser. Patents are the first records in a chain of title to a piece of the Public Domain. Therefore, they are extremely important in establishing private ownership of land. The United States of America acquired the land, by treaty or purchase nevertheless the acquired land had a treaty with the land in one form or another, and with any transaction of the land the treaty followed with it. When the territories where eligible for statehood, the condition for admission to the union was to surrender their land to the United States of America under an Enabling Act. The Enabling Act requires that all of the unappropriated (non-patented) lands be forever granted to the Union for its disposition.

Without such transfer of control over the right and title to the land, there would be no effective authority in a land patent sealed under the signature of the President. The President signed the patents securing the patent rights to the patent holders and to their heirs and assigns forever.

Before March 2, 1833; all original patents were actually signed by the President of the United States; after that, designated officials signed in his behalf. The earliest patent signed by a President is dated at Philadelphia, March 4, 1792, signed by President George Washington and countersigned by Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson.

There are many more cases where the United States Supreme Court has supported the fact that the Land Patent certifies absolute and supreme title to land. There are no cases where the courts ever ruled against the properly obtained Land Patent.

The case of Summa Corp. v California, 466 US 198, is one of the best cases describing how land patents work. For the 1984 case the court noted that they had ruled the Land Patent is supreme title to land. The case was one where California was granted the tidewater lands in the California Republic Constitution and therefore California went after a family’s land, which land was secured under patent on an Old Spanish Land Grant. Interestingly, the case doesn’t talk much about land patents; it talks about the Guadeloupe Hidalgo Treaty. This land patent case speaks mostly about the supremacy clause of the Constitution, Article six paragraph two and with the support of paragraph three; “This Constitution, and the laws of the United States which shall be made in pursuance thereof; and all treaties made, or which shall be made, under the authority of the United States, shall be the supreme law of the land; and the judges in every state shall be bound thereby, anything in the Constitution or laws of any State to the contrary notwithstanding.”

Public Land History

1776 The Declaration of Independence after the Revolutionary War sovereignty came to the land.

1783 Treaty of Paris was signed. This gave the United States over 270 million acres of lands East of the Mississippi, not including the original 13 colonies. These lands were to be used as payment for soldiers who had fought in the Revolutionary War.

1785 The Land Ordinance was created to handle the land growth. Public domain lands northwest of the Ohio River were to be surveyed into 36-square mile townships, and sold at no less than $1 per acre in tracts no smaller than 640 acres.

The Ordinance also reserved Section 16 of each township for the maintenance of schools; set aside lands for Continental Army bounties (changed in 1796); established the minimum price per acre; and minimum land quantity which could be bought.

The Ordinance further established that legal sale and settlement of the public land could not occur until the land had been surveyed and the survey accepted by the Federal Government.

1787 Sale of first public lands directed by Congress as soon as four of 'The Seven Ranges' in the Northwest Territory had been surveyed. At irregular, but well-advertised periods, at the office of the Board of Treasury in New York City, lands indicated on plats were offered for sale to highest bidders over the minimum price of $1 per acre.

1788 First patent issued to John Martin on March 4th for 640 acres in what is now Belmont County, Ohio.

1793 Eli Whitney's cotton gin helped in the settlement of the States of Alabama, Mississippi, and parts of Louisiana and Arkansas.

1793-1823 Land size continued to grow and people moved west. Homesteaders, miners, and new towns began to take over lands they wanted surveyors trekked through unexplored territories to measure and describe what they saw.

1800 The Credit Act of May 10th authorized the sale of land for no less than $2 per acre and could be paid in four installments. The buyer would deposit 5% of the purchase price plus survey fees, at the time of sale. Within 40 days he had to pay an additional 20 percent of the purchase money. Additional payments of 25 percent of the purchase price were to be made within two, three, and four years after the date of the sale. For the last three payments he was charged 6 percent interest per year.

1803 Louisiana Purchase from France doubled the size of the nation, adding the region drained by the Mississippi River's western tributaries.

1812 The General Land Office was created.

As part of the Treasury Department to handle and dispose of public lands the general land office was created and all the land records were now in one place. After the British burned Washington, D.C. during the War of 1812 the General Land Office records were moved to a more fireproof building.

At District Land Offices, tracts of surveyed public lands were sold at auctions to the highest bidder - at or above the minimum price set by Congress. Auctions were held irregularly and sometimes lasted two weeks - if enough prospective bidders attended. After auction, unsold lands were available indefinitely at over-the-counter sales at minimum price.

1818 Red River Valley of the North added to the United States by the Convention of 1818, which set the boundary with British Canada between Lake Superior and the Rocky Mountains at the 49th Parallel.

1819 Florida acquired by treaty with Spain, redrawing the western border of the Louisiana Purchase.

1820 Public land sales boomed.

The Act of April 24, 1820, authorized land to be sold for a minimum of $1.25 per acre and tracts as small as 80 acres. Public lands initially offered for sale by District Land Offices were sold at pre-announced, scheduled public auction. If any land remained unsold, the parcels would be available for purchase at the minimum price on a first-come-first-served basis. This replaced the credit system. This act was used the most it gave all of the rights, privileges, immunities, and appurtenances, of whatsoever nature forever.

The President of the United States signed land patents, giving people title to the land. Hundreds, then thousands of Americans gave up their American nationality and chose to go under Mexican rule in order to get land in Texas for growing cotton.

1825 The Erie Canal opened.

This canal connected the Hudson River in New York with the Great Lakes and provided a water route all the way to Wisconsin. This lured many New Englanders and New Yorkers westward. 1845 Texas became a State but did not give unoccupied lands to the United States. There are no Federal public lands in Texas.

1846 Oregon Compromise with Great Britain ended the joint occupation of the Oregon Country by dividing the region along the 49th Parallel.

1848 Discovery of gold in California.

Mexico gave up a vast territory in the Southwest, providing the U.S. with 338 million acres of public lands - now California, Nevada, Utah, Arizona, and parts of New Mexico, Colorado, and Wyoming.

1849 U.S. Department of the Interior was formed.

1850 The United States purchased 75 million acres of land from Texas, part of what is now Arizona and New Mexico.

1853 The United States purchased 19 million acres of land from Mexico with the Gadsden Purchase. This became part of New Mexico and Arizona.

1862 Homestead Act. Allowed settlement of public lands and required only residence and improvement and cultivation of the land. Any person, a citizen or person intending to become a citizen, 21 years of age or older, and the head of a household could make application. With five years residence and improvements/cultivation, only a $15.00 fee was required to get 160 acres. The Homestead Act was repealed in 1976.

1865 Petroleum reported on public lands at the land office for Humboldt, California. The first reservation of petroleum on public land.

1866 The Mining Act declared all mineral lands of public domain free and open to exploration and occupancy. The GLO established mineral survey districts. Prospectors could file a claim on mineral vein or load at GLO for $5.00 per acre.

1867 Alaska purchased from Russia, adding 365 million acres of public lands to the United States.

1870 Placer Mining Act. Permitted survey and sale of placer mining lands for $2.50 per acre.

1872 General Mining Law passed. This identified mineral lands as a distinct class of public lands subject to exploration, occupation and purchase under certain conditions. First National Park established - Yellowstone.

1877 Timber Culture Act passed granting tracts of public lands to settlers who planted and cared for trees on the plains, repealed in 1891.

1877 Desert Land Act passed permitting disposal of 640-acre tracts of arid public lands at $1.25 per acre to homesteaders if they proved reclamation of the land by irrigation.

1887 General Land Office had 113 district land offices in operation.

1890 Peak number of 123 district land offices in operation.

1898 Annexation of Hawaiian Islands by the United States. Since Hawaii had been an independent nation, no public lands were involved. Principal of public land laws extended to the Territory of Alaska.

1959 Alaska formally admitted to the Union as the last public land state. Hawaii formally became the 50th state. Because most of the Hawaiian islands were in private ownership, Hawaii was not a public land State.

Types of Land Patents

The people acquired their land from varies types of Land Patents. The rail road is by far the largest patented landowner in the United States, most of which is still under the original land patent.

Cash Entry

An entry that covered public lands for which the individual paid cash or its equivalent.

Credits

These patents were issued to anyone who either paid by cash at the time of sale and received a discount; or paid by credit in installments over a four-year period. If full payment were not received within the four-year period, title to the land would revert back to the Federal Government.

Homestead

A Homestead allowed settlers to apply for up to 160 acres of public land if they lived on it for five years and proof of cultivation. This land did not cost anything per acre, but the settler did pay a filing fee. Anyone applying for a homestead patent was required to do a mineral examination. If minerals were found within the boundaries they did not pass to the landowner in the patent.

Military Warrants

From 1788 to 1855 the United States granted military bounty land warrants as a reward for military service. These warrants were issued in various denominations and based upon the rank and length of service.

Mineral Certificates

The General Mining Law of 1872 defined mineral lands as a parcel of land containing valuable minerals in its soil and rocks. There were three kinds of mining claims:

• Lode Claims contained gold, silver or other precious metals occurring in veins;

• Placer Claims are for minerals not found in veins; and

• Mill Site Claims are limited to lands that do not contain valuable minerals. Up to five acres of public land may be claimed for the purpose of processing minerals.

Private Land Claims

A claim based on the assertion that the claimant (or his predecessors in interest) derived his right while the land was under the dominion of a foreign government.

Railroad

To aid in the construction of certain railroads. The Act of September 20, 1850, granted to the State alternate sections of public land on either side of the rail lines and branches.

State Selection

Each new State admitted to the Union was granted 500,000 acres of public land for internal improvements established under the Act of September 4, 1841.

Swamp

Under the Act of September 28, 1850, lands identified as swamp and overflowed lands unfit for cultivation was granted to the States. Once accepted by the State, the Federal Government had no further jurisdiction over the parcels.

Town Sites

An area of public lands which has been segregated for disposal as an urban development, often subdivided in blocks, which are further subdivided into town lots.

Town Lots

May be regular or irregular in shape and its acreage varies from that of regular subdivisions. Follow the paper trail of language for it can set you free.

The land within the United States of America came from:

Native American Indians, England, France, Spain, Mexico, Russia, Hawaii.

Key Case Law Supporting Land Patents

Marsh v. Brooks, 49 U.S. 223 (1850)

A land patent is the highest and best evidence of title. No court, agency, or government entity can question or overturn a valid patent.A land patent removes land from public ownership and places it in private hands, making it immune from state interference."A patent is conclusive evidence of legal title, and said title cannot be collaterally attacked."

Gibson v. Chouteau, 80 U.S. 92 (1871)

Land patents issued by the U.S. government are the highest evidence of title and cannot be challenged by subsequent claims or state laws.

"A patent is the highest evidence of title, and is conclusive against the government and all claiming under junior patents or titles." This case confirms that no one, including state governments or third parties, can challenge a properly issued land patent.

Summa Corp. v. California, 466 U.S. 198 (1984)

State governments cannot override federal land patents or impose new claims on patented lands. "Land patents, once granted, pass title to the patentee beyond the power of government control." This case is critical because it shows that state and local governments cannot impose new laws or restrictions that interfere with your land patent.

United States v. Stone, 69 U.S. (2 Wall.) 525 (1865)

A land patent is conclusive evidence of legal title and requires no further proof. "When the United States has executed a grant and issued a patent, the title has passed beyond the power of recall." This case confirms that once a land patent is issued, it cannot be revoked, modified, or interfered with by any entity, including the government.

Fletcher v. Peck, 10 U.S. 87 (1810)

Once land is granted by the government, it cannot be taken back. "A grant is a contract executed, and a contract cannot be repealed."

The government cannot nullify, alter, or revoke a land patent after it has been lawfully issued.

United States v. California, 332 U.S. 19 (1947)

Lands patented under federal authority are protected from interference by state or local governments."A state cannot impose its sovereignty over lands already granted by the United States." This case reinforces the idea that once a land patent is issued, it remains protected under federal law.

Forbes v. Gracey, 94 U.S. 762 (1876)

A land patent conveys full and absolute title, including mineral rights, unless specifically excluded. "A land patent conveys full title to the patentee, including mineral rights, unless a reservation is made in the grant itself." If your land patent does not explicitly exclude mineral rights, then you own them by default.

Payne v. Central Pacific Railway Co., 255 U.S. 228 (1921)

A land patent cannot be collaterally attacked by another party after it is issued."The patent, when issued, is conclusive against the government and all others." If someone tries to challenge your land patent, they must prove superior title—which is virtually impossible unless fraud is involved.

How to Use These Cases for Your Land Patent Claim

If the county recorder refuses to record your documents, cite Gibson v. Chouteau and U.S. v. Stone to prove that a land patent is supreme title and must be recognized.

If a state or local agency tries to interfere with your land rights, cite Summa Corp. v. California and U.S. v. California to prove that state laws cannot override federal land patents.

If someone claims mineral rights on your land, cite Forbes v. Gracey to show that mineral rights belong to the patent holder unless explicitly excluded.

If a government entity tries to revoke or alter your land patent, cite Fletcher v. Peck and U.S. v. Stone to prove that once granted, a land patent is final and irrevocable.

The Land Patent Process

1. You will need to locate the deed to your property. The Township, Range and Section is used to locate the original land patent(s) with the Bureau of Land Management Records Division.

2. Bringing a land patent claim forward successfully requires researching the abstracts of title, making a claim, and bringing the title forward, minus any exclusions (i.e., easements).

3. Update and record your land patent at the county recorder's office. Because bringing forth the true title is pursuant to the common law, you must be a national to claim the rights and title to land. This is distinct from any actions relating to the equitable title and any liens or encumbrances attached thereto.

4. At this point, you should have completed the Steps to Freedom outlined on the Remedy page. We do not recommend that you begin your land patent process unless you have corrected your political status to national.

Land Patent Checklist

The step-by-step process is definitely something that anyone could do; it just takes a bit of time to research the chain of title and to collect the certified copies.

- You will need a certified copy of your proof of ownership. This is usually a warranty deed or quitclaim deed. It will need to have the metes and bounds in the property legal description.

- Using the legal description (metes and bounds) from your deed, obtain from the Bureau of Land Management Records Division three certified copies of the original land patent that corresponds to your land. https://glorecords.blm.gov/search/default.aspx

- Research your property and build a chain of title with one certified copy of every title transfer starting from your purchase and going backwards to the original land patent.

- Create a package that contains these documents:

- Certificate of Acceptance and Declaration of Land Patent

- Certified Copy of Your Deed or Other Proof of Ownership

- Summary of Unbroken Chain of Title

- Public Notice of Land Patent Claim

- Certified Copy of the Original Land Patent

- Post the package on a bulletin board at your county courthouse or any other public building.

- Record your package with your county recorder.

- Your patent process is complete.

Documents to Record

Essential Documents to Record with the County Recorder

Certificate of Acceptance and Declaration of Land Patent (Primary Filing)

Asserts your ownership rights based on the original land patent.

Includes legal land description and references to the original patent.

Certified Copy of Your Deed or Other Proof of Ownership

Should match the original land patent description.

Available from your county recorder or title company.

Summary of Unbroken Chain of Title

Summarizes your chain of ownership from the original patentee to you.

Includes references to each deed transfer.

Certified Copy of the Original Land Patent

Obtain from the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) or National Archives.

Demonstrates the original federal grant of the land.

Public Notice of Land Patent Claim (If required by local law)

Some jurisdictions require public posting of the claim before recording.

This may be a newspaper notice or a physical posting on the property.

Affidavit of Land Patent Interest (Supplemental)

Sworn statement affirming your land and mineral rights claim.

Helps clarify ownership and chain of title in case of disputes.

Supporting Documents

These documents are for your records, these are not usually filed.

Full Title Search Report

Shows a clear chain of ownership from the original land patent to you.

Helps confirm there are no conflicting claims.

Copies of Any Past Mineral Rights Leases or Transfers

Confirms whether mineral rights remain with the land or were severed.

Check county records or BLM mineral rights database.

County Assessor’s Parcel Report

Verifies the land’s legal description, tax status, and current ownership.

Can be obtained from the county assessor’s office.

Mortgage or Lien Release (If applicable)

If you have an active loan, ensure that your land patent filing does not conflict with lender agreements.

If the loan is paid off, request a recorded satisfaction of mortgage.

Bureau of Land Management (BLM) Research Records (For Federal Land Patents)

If your land was patented under federal law, obtain BLM records to confirm patent status.

Search at BLM’s Land Patent Database.

State Land Office Records (For State-Issued Patents)

If your land patent was granted by a state government, check with the state’s land office or archives.

Legal Notice or Quiet Title Action (If Needed)

If your title is disputed, you may need to file a quiet title lawsuit to clear any challenges.

Optional Documents for Added Protection

Homestead Affidavit – If your state offers homestead protections, you may want to file a homestead declaration to prevent certain creditors from making claims against your property.

Common Law Notice to Interested Parties – Can be sent to local government offices, tax authorities, and lenders to inform them of your land patent claim.

Trust or Estate Planning Documents – If you want to protect your land patent rights for future generations, consider placing the land in a trust or private land association.

FAQ's

Does a land patent declaration affect my loan?

Filing a Declaration of Land Patent does not legally change your mortgage or deed of trust. However, some lenders may misunderstand the filing and see it as a challenge to their lien rights. If the lender believes you're trying to remove their interest, it could trigger a default clause or due-on-sale clause (which allows them to demand full repayment).

Best Approach to Avoid Issues

- Do Not Claim to Remove the Lender’s Interest – The loan remains valid even if you file a land patent declaration.

- Use careful wording in your documents.

- Avoid language that suggests nullifying liens or obligations.

- Example: Instead of saying "no entity may claim superior title," clarify that "this declaration does not affect legally recorded financial interests."

- Wait Until the Loan is Paid Off (If Concerned) – If the lender is strict, you might choose to wait until the loan is fully paid before filing.

- Will a land patent remove my property from the tax rolls?

No — a land patent by itself does not remove your land from the property tax rolls in any state.

I discovered that there are mineral rights attached to my land. How does that affect the land patent?

The discovery of mineral rights attached to your land is significant, and how it affects your land patent depends on whether you own the mineral rights along with the surface rights. The mineral rights were reserved by the government or a previous owner before you acquired the land. A third party holds mineral rights separately from your surface rights.

How Mineral Rights Affect Your Land Patent

- If Your Land Patent Includes Mineral Rights (Best Case)

Some original land patents granted both surface and subsurface (mineral) rights to the patentee.

If your patent explicitly includes mineral rights, you have full control over both the land and its resources (unless later conveyed separately).

You should confirm this by reviewing the original land patent and chain of title for any recorded mineral reservations. If mineral rights were never separated, your land patent protects both surface and subsurface ownership.

- If Mineral Rights Were Reserved by the Government

Many federal land patents, especially after the late 1800s, reserved mineral rights for the U.S. government or state.

If your land patent includes wording like "reserving all mineral deposits to the United States," then the federal government retains the mineral rights. This means the government (or an entity it leases to) can legally access and extract minerals without your permission. If mineral rights were reserved by the government, you only own the surface, not the minerals beneath.

If a third party owns the mineral rights. Sometimes, mineral rights were severed from surface ownership before you acquired the land.

- This means a separate entity or individual (like an energy company or previous owner) may legally extract minerals from your land.

Check your deed history and title search to confirm if mineral rights were sold or leased separately.

⚠️ If someone else owns the mineral rights, they can legally extract resources and may have the right to enter your land for mining or drilling.

- If Your Land Patent Includes Mineral Rights (Best Case)

What do I do if there are deeds that were destroyed by fires or floods in my county courthouse?

You would need to write an affidavit of fact with all the details that you have about those deeds and dates of the fires and floods. Then have it notorized and keep it with your land patent package.

What can I do if the clerk refuses to record my land patent package?

One of the main reasons documents get rejected are due to improper formatting. It's best to contact your county probate office and ask for their requirements to properly record documents. Sometime this can be found on their website.

The minute any documents are received by the county recorder they are considered recorded. But if a clerk refuses to record your documents after they have physically received them, and you have complied with all of their formatting requirements, it is considered criminal in accordance with Title 18 USC § 2071, and is punishable by fines and imprisonment. They are possibly violating federal law.

Don't take the documents back after you have placed them on the counter, leave them there. If the County Recorder refuses to record your land patent documents, you have several legal options to challenge their decision and enforce your rights. Here's what you can do:

1. Ask for a Written Explanation

Politely request a written statement explaining why they are refusing to record your documents.

This creates a legal record of their decision and helps you determine if their refusal is based on law or internal policy.

If they refuse to provide a written reason, document the refusal yourself (date, time, name of clerk, and reason given).2. Check State Recording Laws

Every state has laws governing the recording of land documents. Some states have statutes that require recorders to accept all legally valid documents.Example Laws to Reference:

U.S. Supreme Court: Gibson v. Chouteau, 80 U.S. 92 (1871) – Confirms that land patents are the highest form of title and must be recognized.

State Recording Acts – Most states require the county recorder to accept any properly executed document affecting real estate.If the recorder claims they "do not record land patents," show them state laws that require them to record valid land-related documents.

3. Request to Speak with the County Recorder (or Supervisor)

Escalate the issue by requesting to speak with the County Recorder directly (not just a clerk).

If they insist on refusing, ask for a formal letter of refusal so you can challenge it legally.4. Demand Compliance via a Legal Notice

If they still refuse, send them a formal Notice of Intent to File Legal Action, citing:Federal Supremacy Clause (U.S. Constitution, Article VI, Clause 2) – States must recognize federal land patents.

Gibson v. Chouteau (1871) – Land patents remain the highest evidence of title and cannot be ignored.Mail this notice via Certified Mail to the County Recorder and Board of Commissioners.

5. File a Writ of Mandamus in Court (Forcing the County to Record Your Documents)

If the county illegally refuses to record your documents, you can file a Writ of Mandamus in your local court. This is a legal order forcing a government official to perform their required duty.Steps to File a Writ of Mandamus:

Draft a formal legal complaint stating that the recorder is unlawfully refusing to record a valid document.

Cite applicable laws (state recording laws, federal land patent laws, and case precedents).

Request a court order directing the county recorder to record your document immediately.Example Case: Mandamus to Compel Recording

Banks v. United States, 314 F.3d 1304 (Fed. Cir. 2003) – A court may compel a public officer to perform duties if they are unlawfully refusing.

Can't I just use the title search that I received when I purchased the land?

That's actually a good place to start, but title companies won't search all the way back to the original land patent. They really only search 10-20 years back.

My county court house doesn't have a public bulletin board, how do I post my documents publicly?

Think about these alternative ways to post public notice:

1.Publish in a Local Newspaper (Legal Notices Section)

Most counties recognize publication in a local newspaper as a valid form of public notice.

Choose a newspaper of general circulation in your county.

Request proof of publication (an affidavit or receipt from the newspaper).Recommended wording:

Public Notice: I, [Your Name], do hereby declare my land patent for the following property: [Legal Description]. This declaration is made in accordance with federal law and U.S. Supreme Court rulings, including Marsh v. Brooks, 49 U.S. 223 (1850). Any lawful objections must be filed within [XX] days.2. Post at the County Recorder’s Office

Even if the courthouse lacks a bulletin board, ask the County Recorder if they allow public notices to be posted in their office.

Some counties permit posting notices inside the land records office.

If denied, request the reason in writing.3. Post at the County Clerk’s Office or Another Government Building

Some county clerk offices, city halls, or local libraries provide public notice boards.

Post your notice inside a government building where legal notices are customarily posted.4. Post on Your Own Property (Visible Location)

If no public space is available, some landowners post a notice on their property in a highly visible location (e.g., near a roadway or main entrance).

Take timestamped photos as evidence of public posting.5. Record an Affidavit of Public Notice

If no physical posting is possible, draft and record an Affidavit of Public Notice at the County Recorder’s Office.

This sworn statement serves as proof that you made the notice publicly available.6. Publish Online (Backup Notice)

While not always legally required, posting online (e.g., your website, a public forum, or social media) adds visibility and documentation.

Some courts accept public records databases or legal notice websites as proof of public notice.Choose at least two public notice methods to strengthen your legal position.

Keep copies of all notices, publication receipts, or affidavits for future reference.

Document the refusal if a government office declines to allow posting.

- Are there states that don't have land patents that can be brought forward?

Every U.S. state that was admitted to the Union has land patents. While no state is completely excluded, you can’t bring forward a land patent in these situations:

1. Land Was Never Part of the Public Domain

- Land conveyed before the U.S. held it (e.g., colonial land grants from Spain, France, Britain)

- Common in the original 13 colonies and some parts of Texas and California (Spanish/Mexican land grants)

2. Land Was Patented but Is Now Subdivided or Severed

- If your land is in a modern subdivision, it may be many levels removed from the original patent.

- You can still try to reconnect it through chain of title — but it takes more effort.

3. Federal Land Still Held in Trust

- Military bases, federal parks, or land never released for private ownership

- Tribal trust lands (held by the U.S. on behalf of Native Nations)

Suggested Reading